Reflections of our current and future human freedom in code

Humanity has always been shaped by its inventions. From the first stone implements to the internet, technology has continuously reshaped and expanded the contours of our autonomy. Arguably, the rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI) — more than any previous technology — represents a profound tectonic shift. This rapidly evolving technology is not designed to merely serve us but to be us. It is within this transformative shift that we face the fundamental question:

How can AI be developed and governed to protect and enhance human autonomy, ensuring both freedom of thought and freedom of action?

To answer this, we must explore the philosophical dimensions of autonomy, as well as the socio-political, technological, and psychological boundaries within which this shift is occurring. Equally, a true understanding of autonomy in the digital age requires confronting the complex web of inequality, surveillance, and environmental degradation which underpin its development. At the heart of this inquiry, we face the question of power: Who wields it, who benefits from it, and who is marginalised by this new technology?

Imagine living in a world where every article you read, every idea you consider, and every action you take is monitored by AI, which slowly builds a detailed profile of you with each interaction. Echoing Foucault’s warnings about institutional control, this algorithmic determinism extends far beyond mere consumerism — it holds asymmetric control over knowledge itself. This profile not only shapes what you buy but influences your education, development, and even your fundamental understanding of reality. What once occurred at the institutional level has now permeated every granular detail of individual transactions, with AI subtly steering your decisions and behaviours. This is not just a ‘digital Panopticon’ ; it’s a more advanced and insidious version, where surveillance merges with manipulation — a vision that would leave even Bentham himself unsettled.

In the age of the ‘AI revolution’, we must ask ourselves: what keeps us truly human? And even more provocatively — can we harness AI to be morehuman? “Condemned to be free”, we are defined by and bear the burden of our infinite choices and decisions. Yet, in an overstimulating, ever-changing, and increasingly narcissistic world, we face the palpable tension between this freedom and the deterministic nature of artificial intelligence. After all, AI operates on predetermined patterns derived from (often incomplete, biased, and at times stolen) data, seemingly narrowing the scope of our autonomy — that is, our ability to govern ourselves, make independent choices, and act according to our values and desires without undue external influence or coercion.

Yet, when in the name of convenience we offload many of our choices — from the mundane to the most creative — our autonomy risks becoming a mere illusion, pushing us into a space of passive consumption, void of deeper reflection and moral development. Furthermore, while some AI companies have specifically set out to combat isolation amid the loneliness epidemic, we are noticing that gradually, AI-powered products are assuming roles traditionally filled by humans — those of friends, lovers, and therapists. This shift, though seemingly helpful in alleviating loneliness, raises questions about whether our increasing reliance on AI for emotional and relational support might further erode our autonomy. As these systems evolve, they will become more than tools; they will influence, and may even dictate our daily lives. Whether through targeted fraud, sextortion, or subtle, friend-like influence on our thoughts and behaviours, AI will fundamentally shape how we seek, interpret, and act on information. We risk failing to act in accordance with our ‘second-order desires’ — our capacity to reflect on and choose based on deeper values. One may argue that this pulls us away from Heidegger’s dasein (or being), leaving us in danger of losing the very freedom that defines us.

One challenge lies in the fact that much of our conversation around autonomy is shaped by a pre-scientific understanding of the concept. Stephen Cave argues that natural free will — the ability to navigate complex decisions in an ever-changing environment — is not a mystical trait but an evolved capacity. Like animals making decisions, our freedom exists in degrees, determined by the number of options available to us, how well we evaluate them, and our ability to act on those decisions. He argues that, just as we measure intelligence (IQ) and emotional intelligence (EQ), a Freedom Quotient (FQ) can help us measure how free we truly are in our rapidly changing world.

Beyond AI’s impact on autonomy in the age of algorithmic control and determinism, we must also consider the significant political and ethical challenges which AI’s governance pose to existing power structures. After all, the current development and deployment of these technologies are dominated by a few major tech corporations. Some scholars describe this as ‘technofeudalism’ — a situation where control over AI technologies, data, and their economic benefits are concentrated in the hands of an elite few.

Republicanism, which emphasises freedom as non-domination, offers a powerful critique of this dynamic. For Republicans, true freedom does not merely consist of being free from interference; it requires that individuals are not subject to arbitrary power or control. In the context of the ‘AI revolution’, domination occurs when opaque systems possess unchecked control aspects of our lives — whether through predictive policing algorithms, automated hiring systems, or credit scoring algorithms — without providing avenues for understanding or contesting those decisions. From the algorithmic shaping of political discourse to China’s social credit system, which dictates access to services and opportunities through constant AI-driven surveillance, these instances reveal the insidious nature of ‘surveillance capitalism,’ where AI exacerbates inequalities by consolidating power in the hands of a few.

The ‘AI revolution’ as we commonly hear it referred to is not a real revolution. It is less about overthrowing order and bringing radical change. If anything, it appears to entrench and preserve conservative power structures. Under the guise of innovation, these systems deepen financial and informational inequalities, all while repackaging anti-black, anti-poor, and chauvinist biases as progress. Echoing historian and ethicist Penn, the ‘AI revolution’ is indeed deeply political — but not in the transformative or liberating ways it claims to be.

Crucially, any discussion around autonomy in the age of AI is incomplete if it fails to address the long-term environmental impact of this technology. Its development is highly resource-intensive, particularly in terms of the energy consumption required for large-scale data centres, which significantly contribute to carbon emissions. To give an example, training large AI models can emit over 284 tons of CO₂ — equivalent to the lifetime emissions of five cars. Similarly, generating a single image with certain AI tools can use the same amount of energy as charging a smartphone hundreds of times. As AI becomes more widespread, this ecological footprint must be considered in any ethical evaluation of its impact on human autonomy and sustainability.

Here, Rawls’ “just savings principle” argues that present generations have a duty to ensure resources and opportunities are preserved for future generations, emphasising the responsibility to maintain an environment conducive to human flourishing. Unsustainable AI development, with its significant environmental costs, threatens to undermine this obligation by exacerbating climate change and depleting resources, thus compromising the autonomy of those yet to come. In parallel, virtue ethics highlights the importance of cultivating virtues like foresight and care, which call for conscientious stewardship of technology and resources for the well-being of future societies. Therefore, any governance framework must also ensure that AI’s environmental costs do not erode the autonomy of generations to come.

Practical solutions to the individual, societal, and environmental threats of AI

Having confronted some of the risks AI poses to individual, societal, and environmental autonomy, it is clear that the challenge is to design technologies that actively facilitate meaningful choice. The following six solutions, informed by ethical reflection, psychology, philosophy, and current technological frameworks, offer pathways to protect and enhance human autonomy.

Ensure environmental accountability. AI governance must incorporate energy-efficient algorithms and promote the use of renewable energy in data centres. Cutting-edge approaches like AI-driven energy optimization — such as reducing energy use in data centres by 40% — demonstrate how AI itself can reduce its ecological footprint. In addition to adopting federated learning to reduce energy-intensive data processing, quantum computing offers the potential to drastically cut the energy consumption of large-scale AI models. Lastly, establishing certifications may introduce powerful normative influences and incentivise companies to adhere to long-term environmental sustainability standards.

Decentralise AI systems. Prevent monopolisation by promoting open-source, decentralised AI systems that empower communities to democratically control and govern technology. Federated AI networks allow local data processing, reducing central control and enhancing privacy. Blockchain technology and DAOs (Decentralised Autonomous Organizations) can offer transparent, distributed governance models where decision-making is shared, increasing accountability and reducing monopolistic influence.

Preserve human judgement through dynamic systems and algorithmic silence. Scholars argue that certain decisions, especially those involving moral or emotional complexity, should remain within human control rather than automation. The concept of algorithmic silence suggests that in fields like healthcare, legal rulings, and education, AI can offer data-driven insights but must not override human judgement. By ensuring that human oversight is maintained in ethically charged areas, we can safeguard autonomy and uphold moral integrity in critical decision-making processes. To strike a balance between routine decisions and moments that require deep reflection, AI systems could also incorporate dynamic autonomy levels that allow users to adjust the degree of AI intervention. Through user interfaces, individuals can choose when to rely on automation for routine tasks while scaling back AI involvement in more personal, ethically complex decisions. This flexibility preserves user control at crucial moments, ensuring that AI aids decision-making without diminishing human agency.

Build trust through explainable AI. Explainable AI (XAI) ensures transparency by providing clear, understandable explanations for algorithmic decisions. Tools like LIME and SHAP help break down complex AI models into comprehensible components, allowing users to see how AI decisions are made. Recent advancements such as ‘counterfactual explanations’ and ‘integrated gradients’ offer even more refined methods for interpreting complex neural networks and decision trees. By enabling users to scrutinise and question AI outputs, XAI fosters greater trust in AI systems. This transparency is crucial not only for enhancing user autonomy but also for ensuring accountability in critical applications such as healthcare, finance, and criminal justice.

Foster democratic AI governance. To safeguard autonomy and freedom of thought, AI governance must be democratic and participatory. Collective dialogue, as seen in peace-building processes, offers a model for inclusive, iterative policy development. Tools like Remesh and POLIS, which scales public deliberation through AI-supported consensus-building, and GPT-4-powered pipelines, capable of translating collective input into representative policies, demonstrate how AI can facilitate democratic engagement. Additionally, platforms like Jigsaw’s Perspective AI foster constructive dialogue, ensuring diverse voices influence AI policy. By integrating citizens into these decision-making processes, AI governance can better reflect the plural values of different communities.

Prioritise marginalised communities. To ensure AI promotes autonomy for all, it must prioritise marginalised communities, who are most vulnerable to being left behind by rapid technological advances. AI systems often perpetuate biases that disproportionately harm underrepresented groups in areas like race, gender, and socioeconomic status. Here, the Freedom Quotient (FQ) offers a lens to measure how AI systems truly affect the autonomy of marginalised communities. Moreover, algorithmic impact assessments can help identify and mitigate biases, ensuring AI benefits everyone, not just the privileged few. By using AI to expand access to essential services like healthcare and education, we ensure autonomy is not merely a privilege for few but a fundamental right extended to us all.

Human flourishing at the core of technological transformation

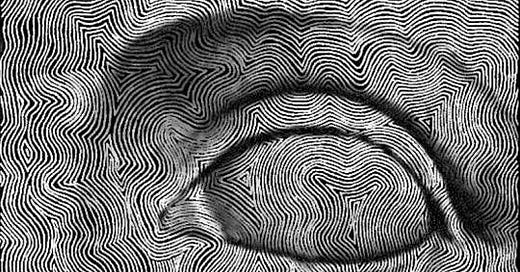

It is perhaps for the first time in history that technology holds up a mirror to us, reflecting not only who we are but who we could become. The challenge is not merely in governing AI, but in governing ourselves to ensure that we do not lose sight of the human values that make autonomy, freedom, and flourishing possible.

At the heart of the AI-autonomy debate lies a tension reminiscent of the age-old philosophical struggle between determinism and free will, a modern echo of what Descartes’ famous dictum, “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”) — which often circulates in its incomplete form. Instead, Descartes emphasised, “dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum” — “I doubt, therefore I think, therefore I am.”. Yet, critique of the ‘transparency society’ warns of the domination of positive power — excessive action, data, and visibility — leaving little room for reflection. Han emphasises that protecting this negative space is crucial for preserving human autonomy, where contemplation and decision-making can thrive in the face of AI’s deterministic operations. This is where compatibilism — a philosophical view that reconciles determinism with free will — becomes relevant. Compatibilism posits that while certain events may be determined by external forces (such as AI recommendations based on algorithms), humans can still exercise free will if they have the capacity to reflect on their desires and act in alignment with their true values. Put differently, there is a way for AI to coexist with human autonomy rather than undermine it. By integrating dubito into AI systems through mechanisms that promote self-awareness and reflection, AI can encourage us to hesitate, to question — ensuring that even in a world of algorithmic predictions, we remain agents capable of reflection and choice.

Crucially, autonomy should not be a privilege reserved for the few. Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia, or flourishing, risks becoming a “luxury belief,” accessible only to those who have their basic needs met. AI governance must actively confront and dismantle structural inequalities by redistributing its benefits. This includes expanding access to healthcare, education, and economic opportunities for underserved populations as well as acknowledging the exploited workforce that underpins the ‘faux-tomation’ of AI. The ongoing arms race to superintelligence not only conceals the exploitation of ghost workers but also arguably stifles true innovation, diverting resources toward damage control rather than fostering meaningful, ethical progress. Collective autonomy and flourishing must be central to AI governance, recognising that autonomy is a right, not a privilege, to be extended across societies and generations to come.

Today’s algorithmic traps promise convenience but risk locking us into systems that erode autonomy, mirroring a self-imposed state of hell akin to Dante’s inferno. AI governance must, therefore, foster critical engagement, ensuring technology empowers rather than diminishes human agency. The challenge lies in creating AI systems that actively contribute to human flourishing. This requires more than technical fixes — it demands a philosophical, ethical, and psychological reimagining of AI’s role in our lives, to build systems that empower autonomy and promote flourishing at an individual, societal, and environmental level. Only then can we ensure that AI becomes a tool to help us become more human, rather than a force that controls, diminishes, or replaces us. The challenge is not just managing the rise of this transformative technology, but harnessing it to preserve, expand, and protect the essence of what it means to be human — free in thought, action, and potential.

Note: This essay comes with 50+ footnotes. If you care to dig deeper, drop me a line.